Echoes of history: CB&Q bands brought railroaders together over love of music

By SUSAN GREEN

Staff Writer

If relics from the past could talk, what stories they could tell. When Fort Madison, Iowa, BNSF Division Trainmaster Doug Beckman was gifted two weathered band uniform hats featuring the logo of the Burlington Route, a BNSF predecessor, his interest was piqued but their story unknown.

“A church member who knew I worked for BNSF and have an interest in history sent me the hats, which she thought maybe were her dad’s,” said Beckman. He was able to verify in history books that the Burlington – formally the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad (CB&Q) – indeed had employee bands.

“I wanted to learn more but there just wasn’t a lot of information out there,” he said.

Beckman turned to the Burlington Route Historical Society (BRHS), whose members include historians, railfans, collectors, modelers, photographers and former employees interested in preserving the CB&Q’s history. BRHS magazine and newsletter editor David Lotz helped fill in the gaps.

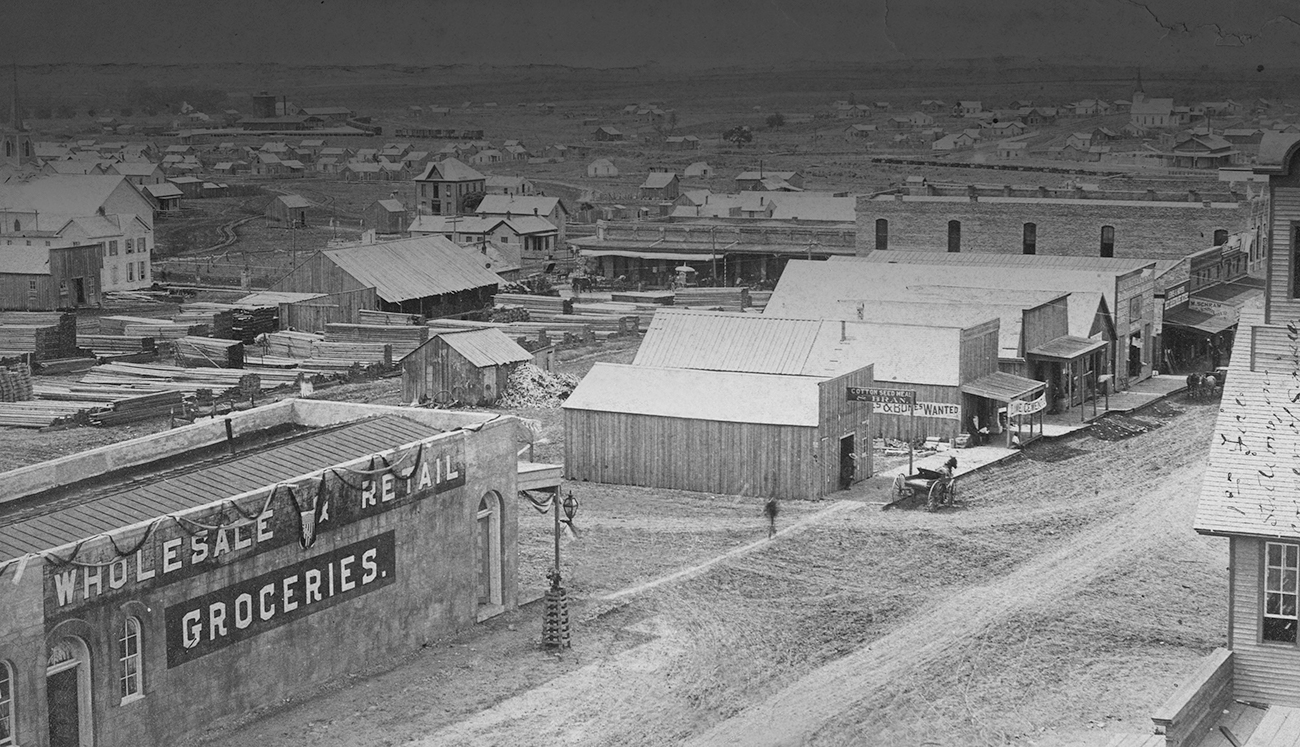

“I was born and raised in Burlington (Iowa), and even though I never worked for the railroad, I want to help preserve its history,” explained Lotz, who knew that nearby West Burlington was home to the CB&Q locomotive and freight car repair shops and sponsored a band. As he did research, he discovered there were other CB&Q bands and dedicated an entire issue of the Burlington Bulletin to the topic.

“There were bands in Lincoln and Plattsmouth, Nebraska, in Hannibal, Missouri, and maybe Denver, plus a chorus in Chicago as well as an all-women’s drum and bugle corps,” said Lotz, who recently learned another band was at Galesburg, Illinois. “Most of the bands formed where there were shops.”

This was in the days before TV, when radios and movie theaters were making their way into homes and towns. Music-making was a way to socialize, especially for those who worked in the shops, where employees typically had one function or station and limited exposure to others.

“It was probably an effort by the shop to build comradery and give employees an opportunity to get to know one another,” Lotz said. “There was also a PR aspect in why the railroad would have supported the bands.”

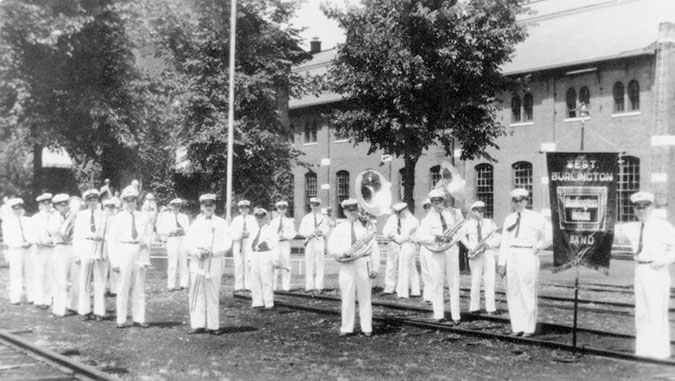

The longest-running band was the West Burlington, which organized in the late 1880s and – following starts and stops during the Depression and world wars – officially dissolved in 1967.

According to Lotz’s research, the West Burlington shop band played for local occasions like company picnics, parades, concerts and celebrations as well as in cities along the Burlington route. When traveling, the railroad furnished the band a Pullman sleeper car because members could spend up to two weeks away from their jobs and homes.

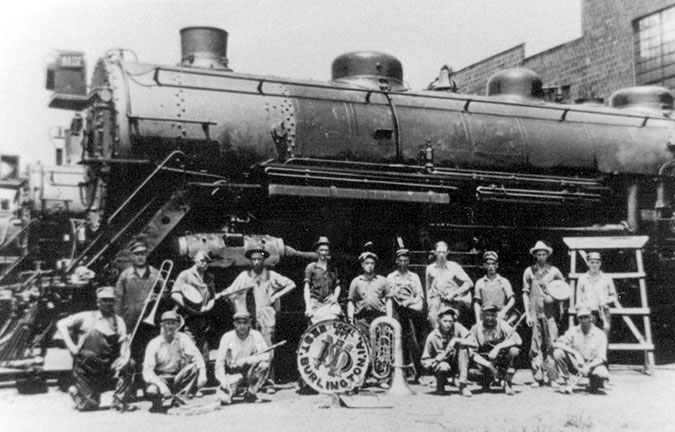

While at home, the West Burlington band, which had 15 to 35 employees, practiced weekly at the shop, playing everything from marches to popular tunes. According to local newspaper reports, there was a Thursday concert at the shop, where “… a score of the men, when they lay down their tools for the noon hour, take up musical instruments. And there, in the shadow of the powerful locomotives or amid the maze of machinery that is used to keep the rolling stock of a might railroad in trim, they give a concert.”

According to the Nebraska State Historical Society, the Burlington Route Lines West Band was organized in 1928 in Lincoln at the Havelock Shops. It, too, was an amateur group of employees (men and their sons) that performed at state and county fairs and local festivals throughout the Plains and at nearly every train depot dedication.

Over the years interest waned, and in 1967 the remaining band members officially disbanded and turned over the band’s funds of $9,000 to the University of Nebraska Foundation to establish an endowment fund for the university bands with preference given to scholarships.

Little is known about the Galesburg band, but newspaper records indicated it began in 1896 and ended in 1904. On a visit to the city in 1899, President McKinley was serenaded by the band, which also played at an annual ball, two excursions to Joliet and Rockford, Illinois, and a political rally in Chicago.

The Burlington Zephyr Chorus was made up of Chicago-area employees, mostly women, and formed in 1943 “to provide enjoyment for Burlington employees who desire to participate in group singing and to provide choral music for the enjoyment of music lovers,” according to a memo.

The chorus of approximately 40 employees included clerks, typists, secretaries and supervisors from the CB&Q headquarters. For many years the chorus performed at churches, schools and civic groups and made several radio appearances and entertained at travel shows.

Over time, most of the bands that had railroad roots disbanded as other forms of entertainment and connection evolved. (One that still performs but is no longer railroad-sponsored is the Topeka, Kansas, Santa Fe band that originated from another BNSF predecessor railroad.)

Today, while the CB&Q bands, like the uniform hats, are part of history, the universal love of music – in all its forms – continues in the 21st century and beyond.